Colin Deeley works for the National Trust and gave a very detailed history of Southwell Workhouse. I had no idea that looking after the poor became a national social issue during the reign of Elizabeth 1st and that it continued until well into the twentieth century.

Elizabeth recognised that poverty was a big problem throughout the country so she brought in the Old Poor Law which forced parishes to provide for their destitute parishioners. As a consequence, coal, food and clothing was supplied to the very poor with the money being provided by the parish ratepayers. By 1775 however, three years of bad harvests had taken its toll, and the price of a loaf of bread had risen to 1 shilling (or £4 in today’s money). This massive rise in costs ultimately resulted in a very, very long queue of paupers needing weekly handouts.

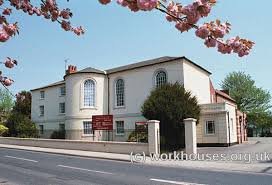

To try and ease the burden on his rate paying parishioners, the Rev John, Thomas Becher of Southwell came up with the idea for his local parishes to combine their funds and build a workhouse which could then house, feed and clothe the destitute in exchange for their labour. The building, which was partly designed by Becher himself, was completed in 1808 to house 84 people.

By 1824, it was decided there was a need to build a larger workhouse; this was originally called the Thurgarton Hundred Incorporated Workhouse but, it was later changed to the Southwell Union Workhouse. Its design and plan was included in Becher’s paper entitled The Antipauper System which he wrote in 1828; this paper was so well received that it eventually resulted in the government bringing in the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834 and building Workhouses around the country.

Belcher’s view was that the Workhouse should only be available to the truly destitute as its regime would be harsh. In exchange for being fed and housed in segregated areas, inmates had to wear a uniform and, all those deemed to be able- bodied were expected to undertake hard manual labour. The building could house up to 158 inmates at any one time comprising men, women and children; the inmates were ‘looked after’ by the Master and Matron who were ably assisted by a clerk, a chaplain, a medical officer and a school teacher. All the staff were employed by a board of 62 Guardians who also made the rules and set the regulations.

The men were expected to work every day in the 6-acre gardens growing fruit and vegetables to supply the kitchen; any ‘excess’ they grew was sold to the public and the money used by the Master to provide the men with ‘little extras’. Able bodied men were also expected to undertake additional work which included crushing stones for road building and oakum picking. Although both of these jobs generated additional income for the Workhouse, they were hard and tedious so it was not uncommon for some men to occasionally rebel. When this happened, the miscreant was put in the refractory as punishment because this also happened to house any dead inmates who were awaiting removal.

Needless to say, bad behaviour did not occur very often and why would it when the inmates were being fed, clothed and housed for free?.

Female inmates were expected to undertake daily jobs including cooking, cleaning and sewing; they also worked in the laundry where they could earn money by ‘doing’ the laundry of ‘outsiders’. The money they ‘earned’ was used by the Master to provide additional ‘perks’ for them in the way of food usually.

The children of the Workhouse were completely segregated from their parents and never allowed to see or speak to them. They were housed in a school room which not only had desks and chairs but also included their beds; it was not uncommon for five children to sleep in one bed sideways on. In the Southwell Workhouse, the children were also taught how to make shoes so they even had a trade they could use in the Workhouse or outside if and when they were ever released.

The inmates’ dormitories were allocated on the second floor of each wing; men on one side and women on the other however, the staff were provided with their own private self-contained accommodation on the top floor of the main building. From here they could look out on the extensive grounds or the inmates when they were ‘exercising’ in the yard. They could also eat what they wanted, when they wanted; the inmates on the other hand, had a very strict timetable and a set menu. Men received more food than the women with meat only being served twice a week, occasionally though, the Master would use the extra money the inmates raised by supplementing the quality and quantity of their diet.

On the whole, life in the Workhouse was regimented, intentionally kept dull,monotonous and stricktly controlled because Becher aimed for moral improvement in the inmates. His view was that making idle folk do hard work would convert them to a more upright lifestyle yet, these inmates had no reason not to comply when everything they needed was being provided so why wouldn’t they do as they were told?

Over the years, Southwell Workhouse was extended and improved upon. In addition to the staff quarters being on the top floor there was also an infirmary with 6 beds plus one for a nurse. In 1913, a garage was built to house two cars plus a stable block to accommodate the Guardians horses, and in 1926, a mortuary was added. Also, in this year a hospital was built to provide services which could not be carried out in the infirmary.

On April 1st 1930, more than 650 Workhouses including Southwell were disbanded and handed over to the local council. All the children were placed in foster homes and Southwell Workhouse was given a new name. When the NHS was created in 1948, the building was partly converted and provided temporary accommodation for the homeless until 1976. In the 1980’s, it became a residential home for the elderly however, by 1997, Southwell Workhouse was going to be converted into flats when the National Trust stepped in and bought it; it is now one of the best-preserved examples of a Workhouse in the country.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.